I think we can all agree that the Pythagorean Theorem is one of mathematics’s most famous theorems.

Now the mention of the Pythagorean Theorem usually has the average denizen jumping to the famous equation of “a2 + b2 = c2“. However, upon being asked about what each variable stands for, they’ll freeze. Additionally, to make matters worse, if any of the variables were to switch on the triangle (for example, having “a” and “c” swap “places”), the original equation is incorrectly used (for the aforementioned example, the one to use instead would be “c2 + b2 = a2“).

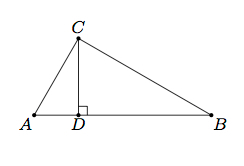

This begs the question of what the equation “a2 + b2 = c2” actually means. Well, “c” represents the length of the hypotenuse, while “a” and “b” represent the lengths of the two legs. The equation summarized in words is thus, “The sum of the two areas of the two squares on the two legs (“a” and “b”) is equal to the area of the square on the hypotenuse (“c”).” A way to visualize this is as follows:

Mouthful, ain’t it? Well you might have heard it said in a slightly different way before. For example, in The Wizard of Oz? Or maybe The Simpsons? The Mathologer talks about how it was said in those two instances in a video which I’ll link here (Note: they said it incorrectly).

Anyhow, any trio of natural numbers that satisfy the Pythagorean Theorem is referred to as a “Pythagorean Triple”. The smallest natural numbers to satisfy the equation are 3, 4, and 5, as 9 + 16 = 25. Thus, the 3-4-5 right triangle is one of the most well known right triangles. Other examples include 5-12-13, 8-15-17, 7-24-25, and 9-40-41. Any trio of numbers that are multiples of another Pythagorean Triple are not considered a Triple themselves (ex: 6-8-10). There happen to be a total of 16 Triples whose numbers are less than 100, as well as an additional 31 Triples whose numbers are less than 300 (for a total of 47).

Before I get to the main feature of this post, I’d like to mention one way to prove the Pythagorean Theorem: by similar triangles. At the same school where I told the quadrilaterals story while student teaching, one of the last few topics I was able to cover was this proof.

The idea behind it is to use proportions, as corresponding sides in similar triangles have their lengths in proportion (CSSTP, similar to CPCTC). In the above diagram, AD/AC produces the same quotient as AC/AB (note that both ratios are equivalent to the sine of angle B, where sine is opposite/hypotenuse in a right triangle). Likewise, BD/BC produces the same quotient as BC/BA (similary, both ratios are equiavelnt to the cosine of angle B, where cosine is adjacent/hypotenuse in a right triangle). Cross-multiplying results in two equations: AC2 = AB x AD and BC2 = BA x BD. Therefore, AC2 + BC2 = AB x AD + BA x BD. However, since AB is just BA, then we can factor the right-hand expression to AB x (AD + BD). Yet, AB + BD is just AB, so what we’re actually left with is AC2 + BC2 = AB2. But this is the Pythagorean Theorem’s equation (AC is “b”, BC is “a”, and AB is “c”). I think you can imagine how shocked the students were at arriving at this (a freshman proving the Pythagorean Theorem?!).

Anyway, back to the title of this post. I bet you were thinking this when you saw “Garfield”:

Turns out, I was actually referring to none other than the 20th President of the United States, James Abram Garfield.

Despite serving the second shortest tenure in the White House (he sadly suffered an assassination attempt about four months in and died two months later from infections caused by his doctors), Garfield was a bit of a genius. Born in a log cabin in poverty in Ohio, he studied law and entered politics in 1857 as a Republican (the same party that Abraham Lincoln would helm 3 years later). He would later serve in the Union Army during the Civil War before beginning a congressional career representing a new district of Ohio.

All the while, Garfield also found a unique way to prove the Pythagorean Theorem. Previously known methods included Pythagoras’s proof by rearrangement, a proof using similar triangles (which I explained earlier), as well as Euclid’s own unique proof. Garfield’s proof would later published in the New England Journal of Education in 1876.

What made Garfield’s proof unique was that it was a trapezoidal one. The proof itself is quite impeccable:

Math historian William Dunham would later note that Garfield’s work was “really a very clever proof”. And I couldn’t agree more. The elegance of separating the trapezoid into triangles and deriving known equations is nothing short of mathematical beauty.

How did I learn of this, though? Well, it goes back to the same class where I learned of the quadrilaterals story at Thanksgiving. Our professor told us that when teaching the Pythagorean Theorem, a homework assignment to give that night would be to tell the students, “Look up the Pythagorean Theorem and Garfield. Tell us what you find tomorrow!” This was the trick: kids would assume Garfield from the comics (as I might have tricked you here) but be shocked that it wasn’t, instead finding that the name actually referred to a rather obscure president. Indeed, given my own fascination with presidents, this definitely tickled my fancy.

Anyhow, the proofs to the Pythagorean Theorem are quite fascinating. The one by similar triangles should be a staple of high school Geometry, although this one also deserves a look during that time as well considering how simple it is.