WARNING: This is a long post.

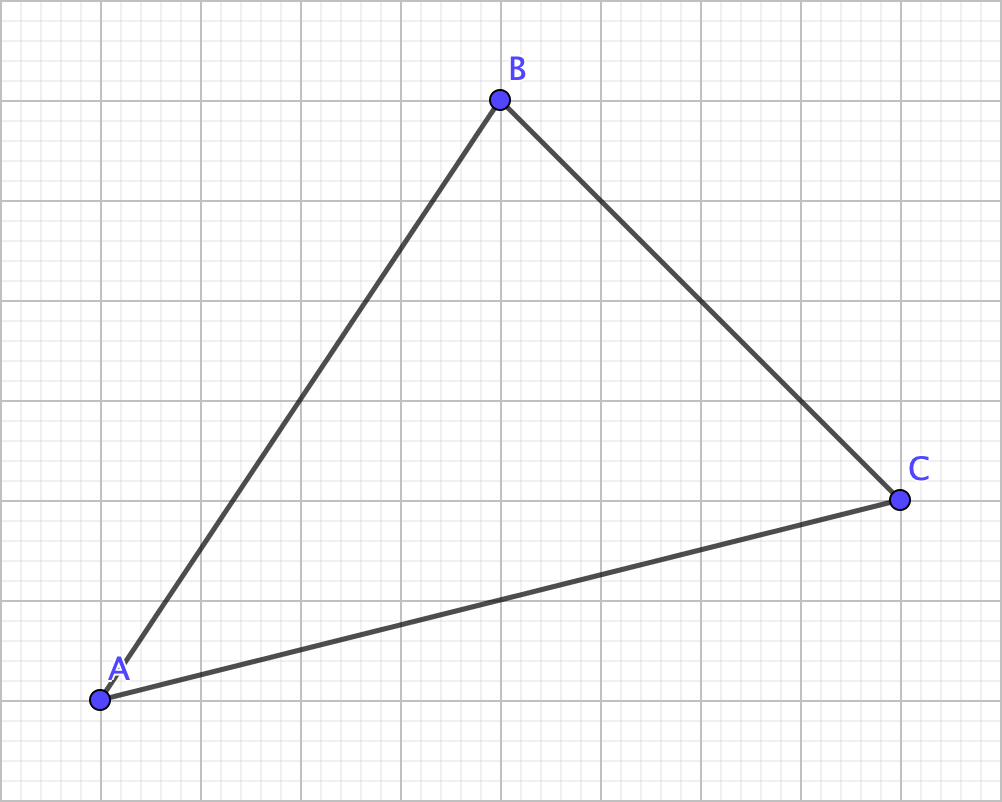

Triangles are the simplest polygon: a closed figure consisting of three vertices (the corners) with line segments connecting them (the sides/edges).

So something as simple as this can actually be crazy? Well based on the last article, it certainly seems that way, because there’s a way to relate the sides. However, that equation only holds for right triangles, so there has to be some way to make triangles in general “crazy”.

Enter the triangle centers. There’s five in total, and I’ll discuss them in length. There are some cool properties that might seem insane at first thought but, when explained, will make sense.

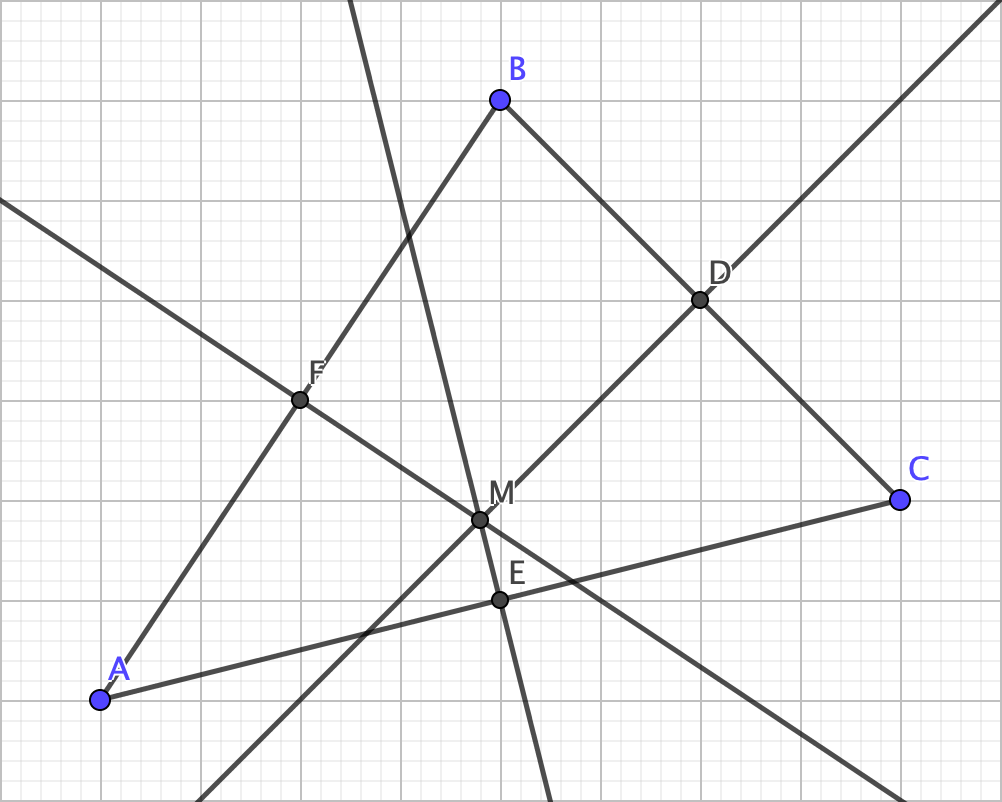

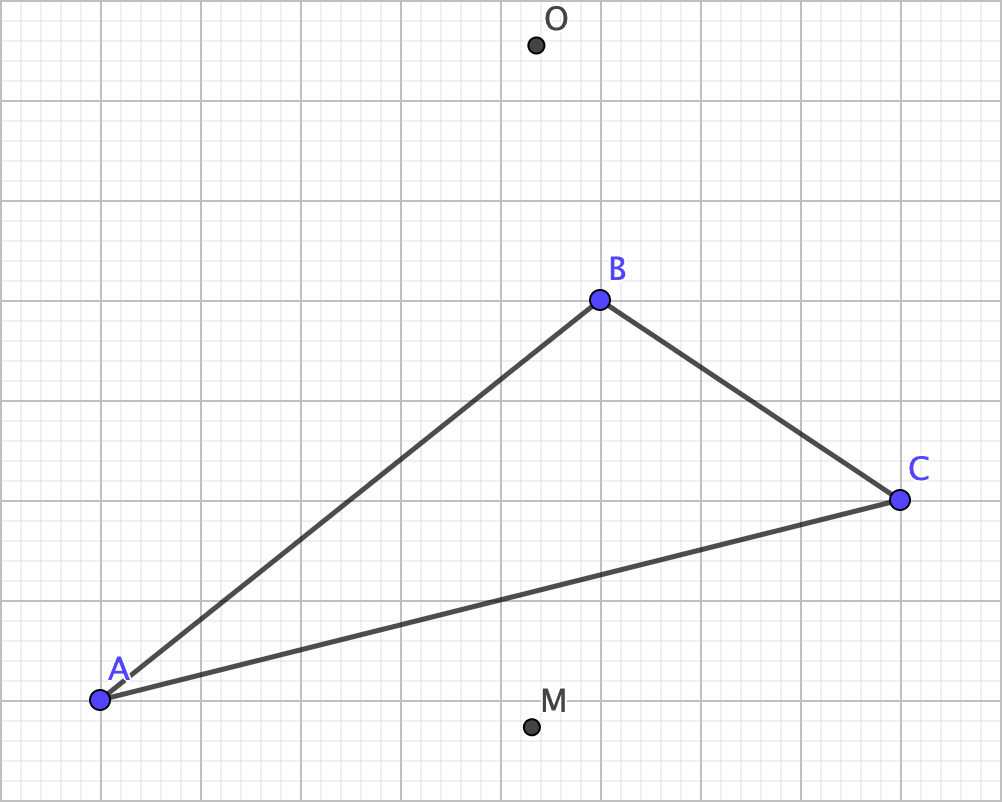

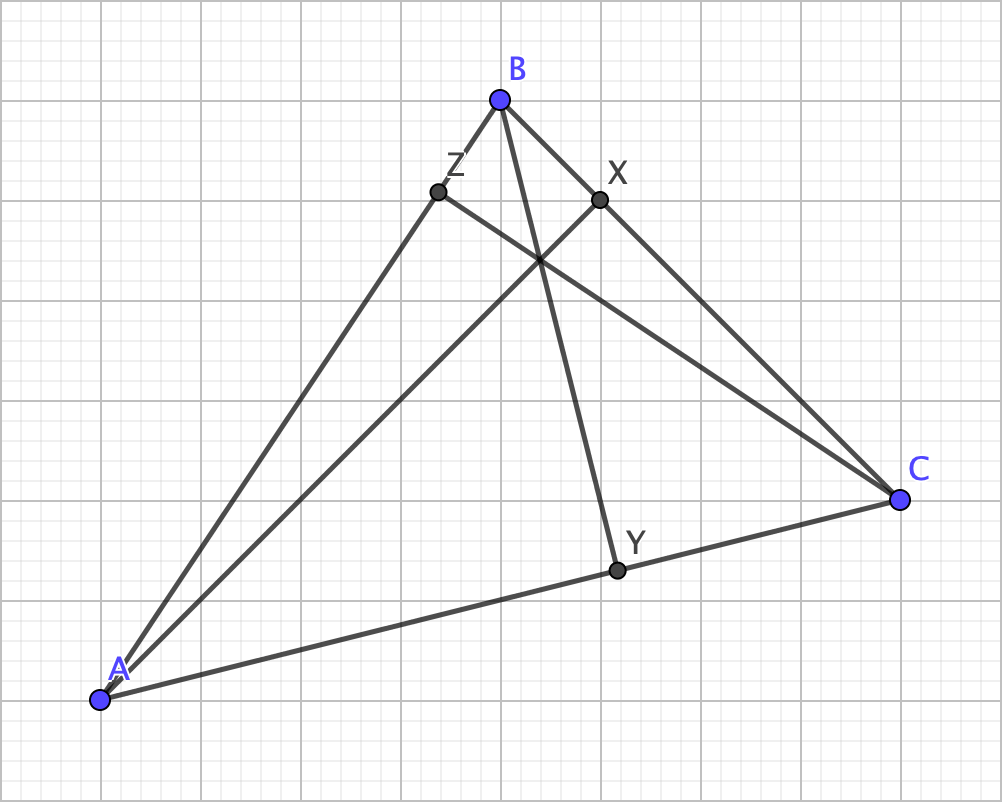

Here’s the first one: the circumcenter, defined as the intersection of the perpendicular bisectors of the sides. Quite a mouthful to read, ain’t it? Well, here’s a visual:

As you can see, the lines are intersecting with the sides at the midpoints and are perpendicular to the sides as well, hence “perpendicular bisector”. But notice how they are all intersecting at the same point. For any triangle, this will be the case: the perpendicular bisectors of a triangle’s sides will intersect at exactly one point.

With that in mind, I’ll drop another bombshell: the circumcenter happens to be equidistant from the three vertices. How so? It comes from the use of the perpdincular bisectors. Given a line segment, any point on a perpendicular bisector is equidistant from the two endpoints of the line segment. Using the diagram, since M is the same distance away from A as it is to B and M is the same distance away from B as it is to C, then M must be the same distance away from A as it is to C, meaning that those three distances are equal.

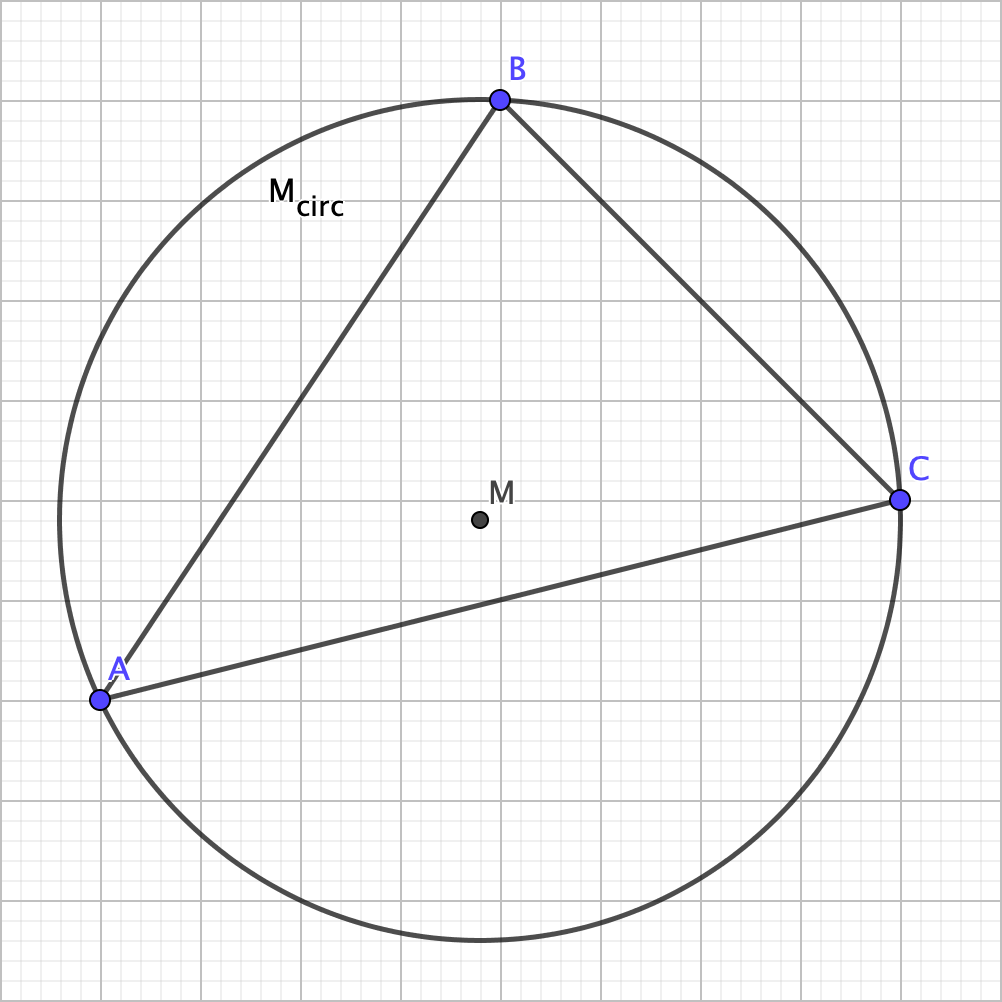

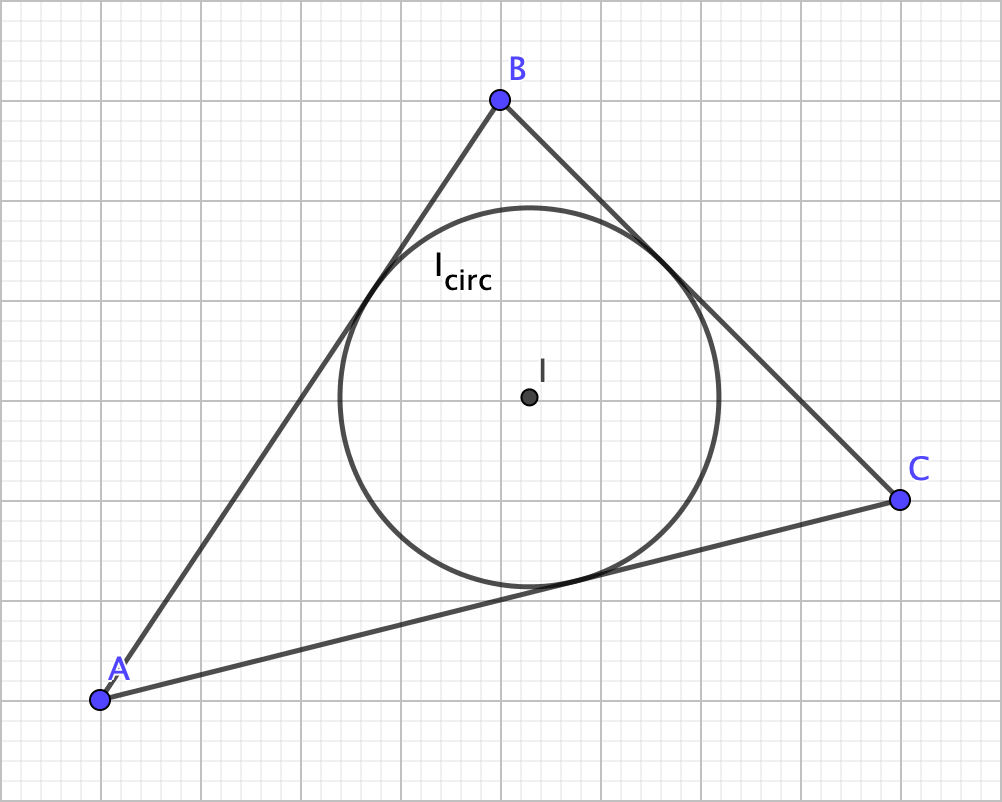

Using this property of the circumcenter allows us to construct a circle such that the three vertices are on the circle (i.e. circumscribe), which we mathematicians refer to as the circumcircle:

How practical is the circumcenter? Imagine three friends who want to meet up but make it so that no one ends up traveling more than someone else. The circumcenter of the triangle that the friends form is where they should meet. However, this might actually be only be practical if everyone is flying, as roads and rails force people onto certain paths (whereas flight gives people a lot more freedom in terms of direction).

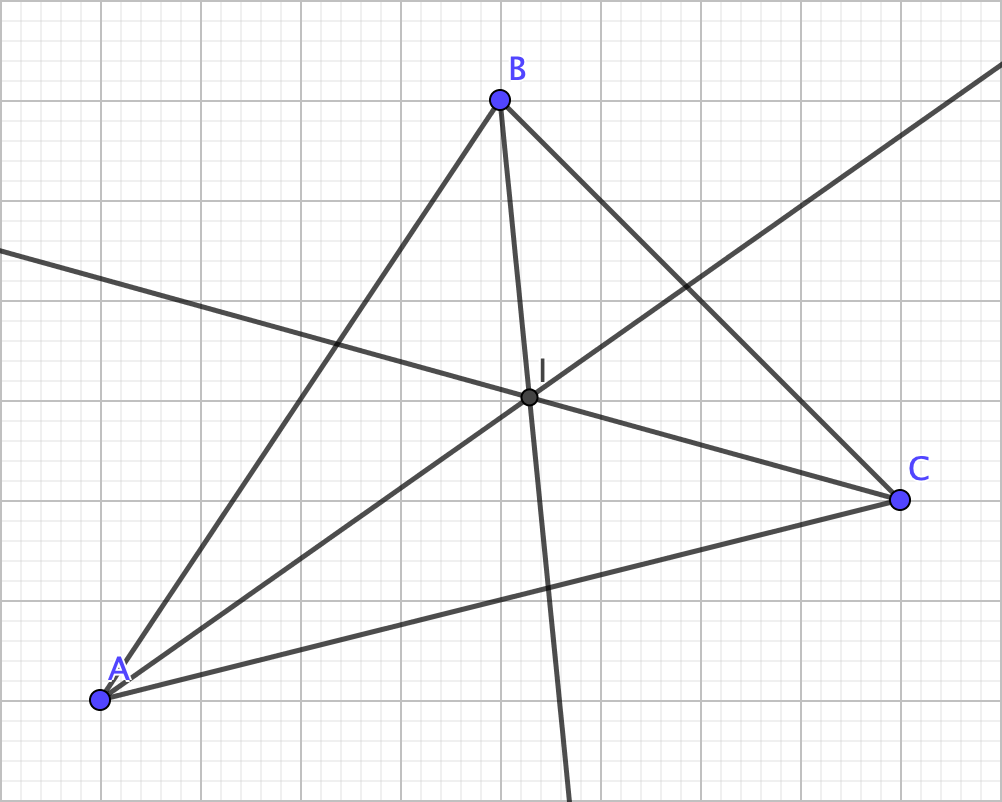

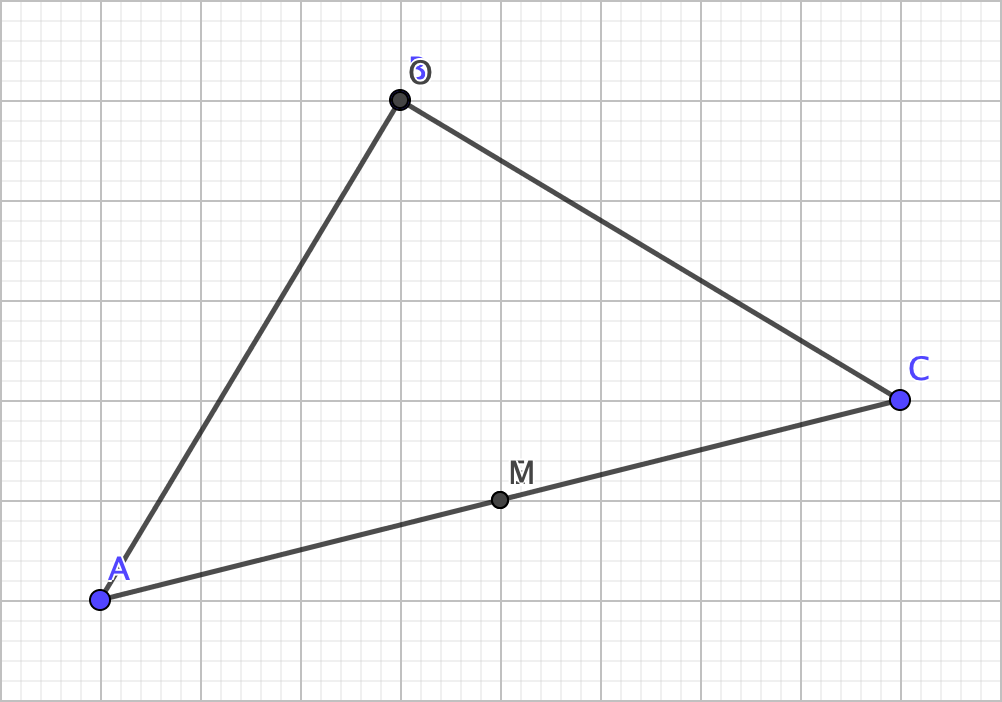

Now, if it is possible to have a circle “surround” a triangle, is it possible to “stuff” one inside a triangle? The answer also happens to be a yes. To do so, we construct the angle bisectors of the triangle. Just like with the perpendicular bisectors, the angle bisectors ALSO happen to intersect at exactly one point, and this point is the next triangle center: the incenter.

A property of angle bisectors is that any point on it is equidistant from the rays that form the original angle. With that in mind, the incenter happens to be equidistant from the sides of the triangle, allowing us to inscribe a circle inside the triangle (the incircle).

Is the incenter practical? Much like with the circumcenter, only in certain circumstances (pun intended). Imagine a triangularly shaped lawn (how odd, right?) where a sprinkler is needed such that no water ends up outside the lawn. The incenter is where the sprinkler would maximize on coverage.

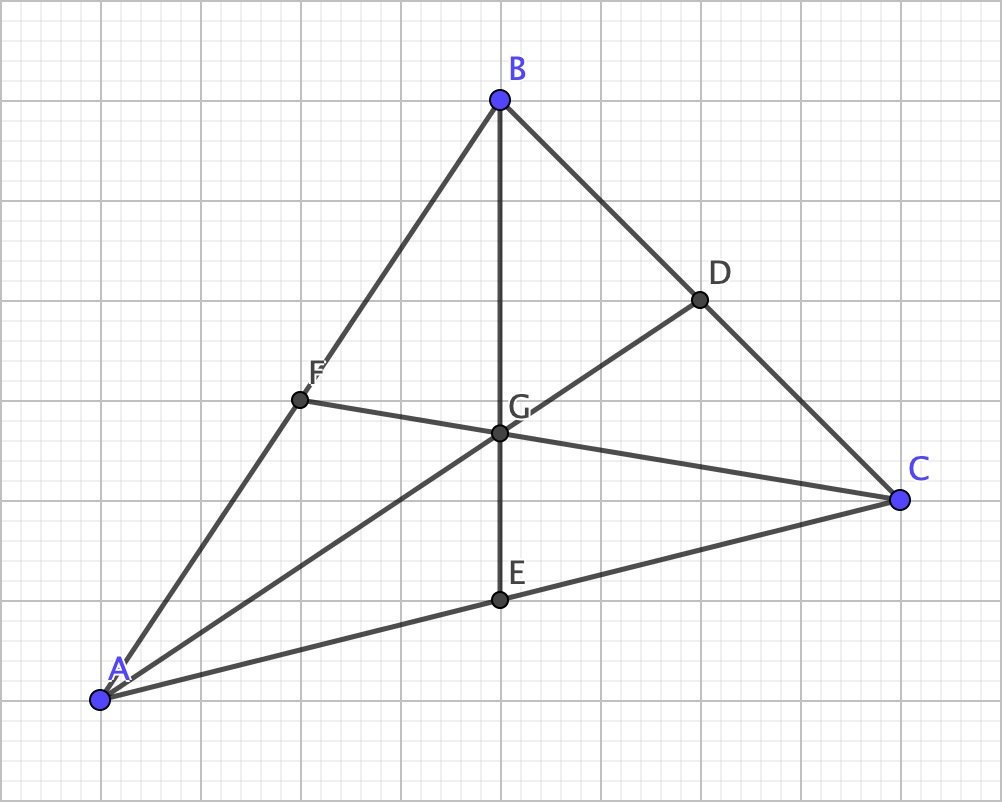

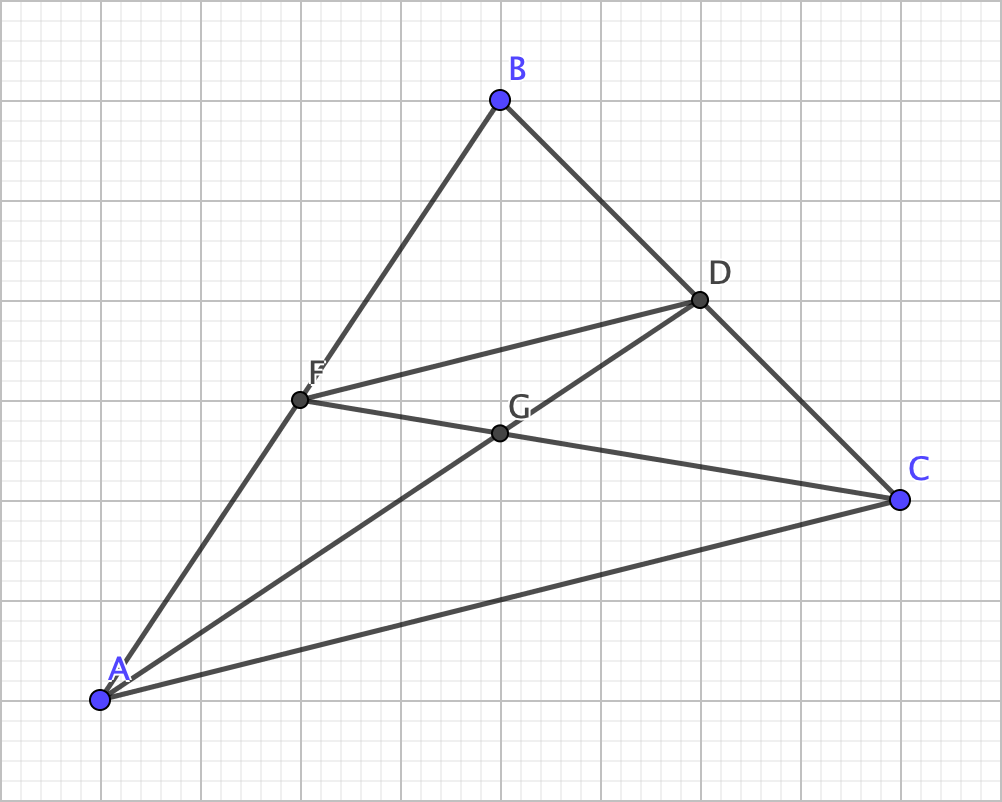

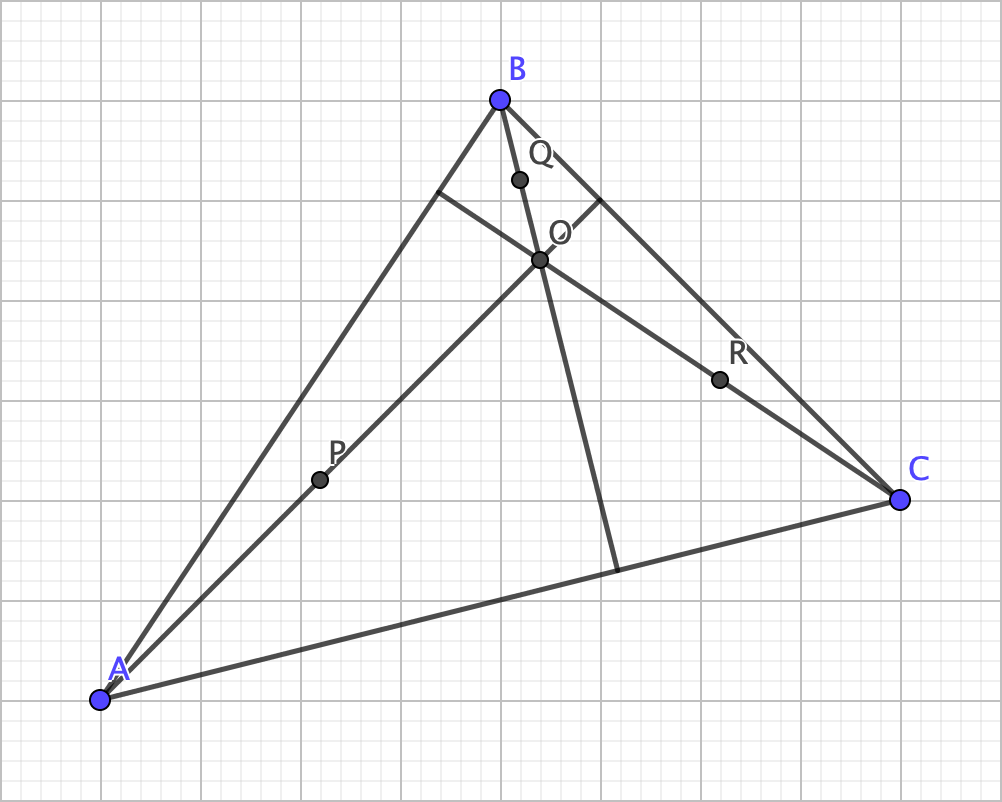

The next triangle center of note relies on the midpoints and simply connecting them to the opposite vertex, and these line segments are referred to as the medians. Almost like magic much like the last two, the medians ALSO happen to intersect at exactly one point, the centroid.

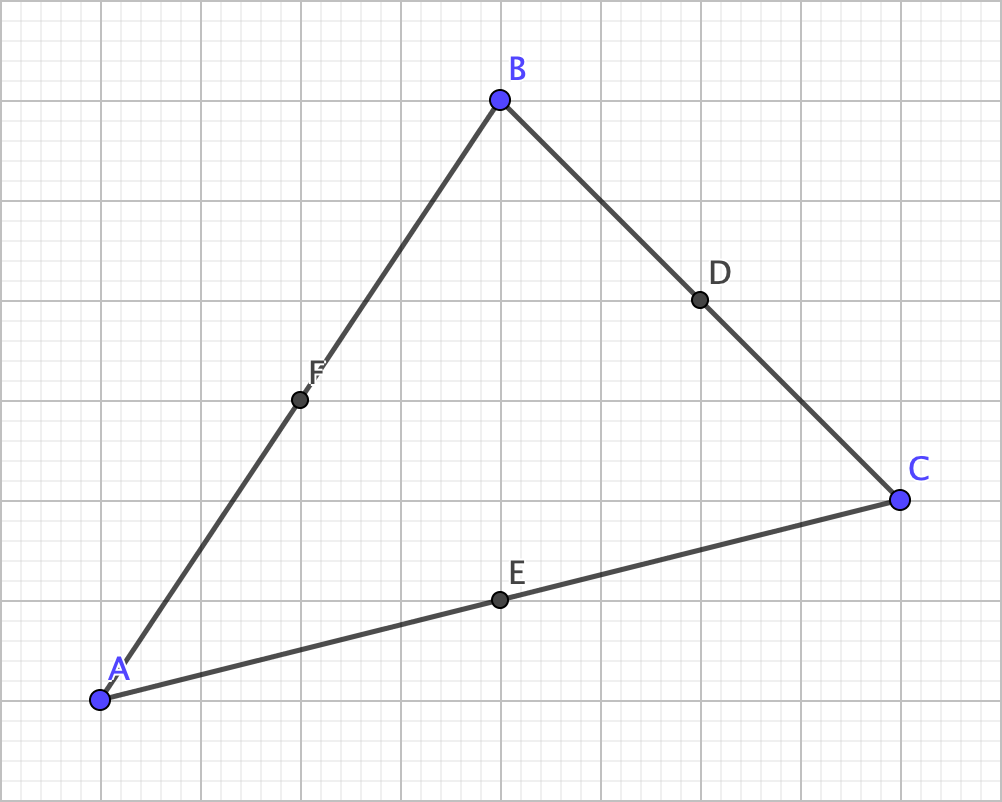

A notable property of the centroid is that it separates the medians into new segments that are in a 2:1 ratio (for example, AG = 2 x GD). How to prove this? Well this all relies on the midpoints themselves and constructing a line segment to connect two of the midpoints to induce a similarity argument.

Here, since D and F are the midpoints of the sides, we can conclude that BC is twice BD and BA is twice BF. Given that angle B is included in those two sides, we can conclude that triangles FBD and ABC are similar and have a side length ratio of 1:2. Therefore, we can conclude that AC = 2 x FD. Additionally, due to the similarity, we can also conclude that the line segments connecting A and C as well as F and D are parallel because of the corresponding angles being congruent (for example, angles BFD and BAC).

Brief segue: why am I not saying “AC” and “FD” for the line segments? If you know your math, you should know those refer to the lengths as opposed to the segments themselves (I’d be using overlines if I could, but I can’t because WordPress)!

Anyway, the next part involves using the two medians as shown. As angles DGF and AGC are vertical, they are congruent. Next, because because the line segment connecting A and C and the line segment connecting F and D are parallel, angles GDF and GAC must also be congruent as they are alternate interior angles, thereby making triangles GDF and GAC similar with a side length ratio of 1:2. Thus, AG = 2 x GD and CG = 2 x GF. Likewise, the same process can show that BG = 2 x GE.

The centroid is probably the most practical (at least in my opinion) of the triangle centers, as it represents the center of gravity for the triangle. By cutting out a triangle out of paper, you can balance it perfectly on the tip of a pencil should you find where the centroid is. Another example would be like making a triangular table and having it stand on just one leg: the leg is best placed on the centroid to allow the table to properly balance.

The next center is probably the least noteworthy: the orthocenter. Much like with the others, it’s found by finding the point of intersection of the altitudes. An altitude of a triangle is found by constructing a line segment that connects a vertex with its opposite side such that it is also perpendicular to the side (the side may have to be “extended” if the triangle is obtuse):

Why is the orthocenter not particularly noteworthy? Well, there aren’t really any practical uses for it. In fact, it’s only really used to find the last center. However, there is one noteworthy property of it. In fact, this property also applies to the circumcenter: it may not actually be in the triangle:

This can only happen if the triangle is obtuse. What if the triangle were to be right?

Well that’s something. Also, note how the orthocenter and circumcenter are coinciding with other points on the triangle. Fascinating, isn’t it?

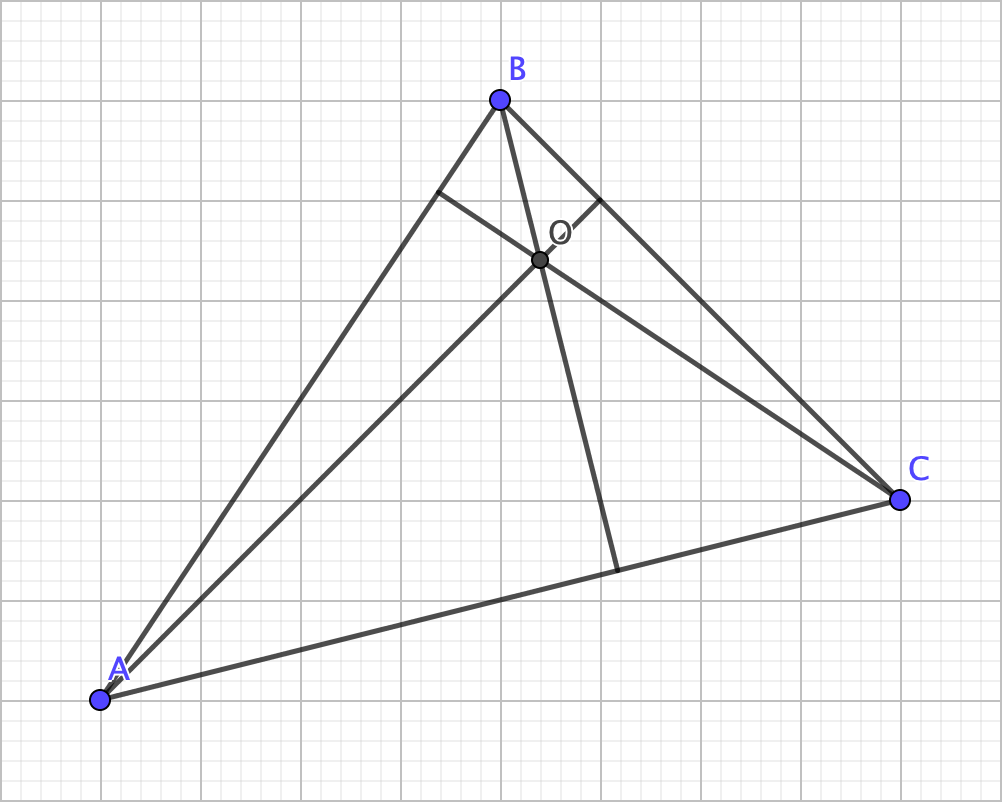

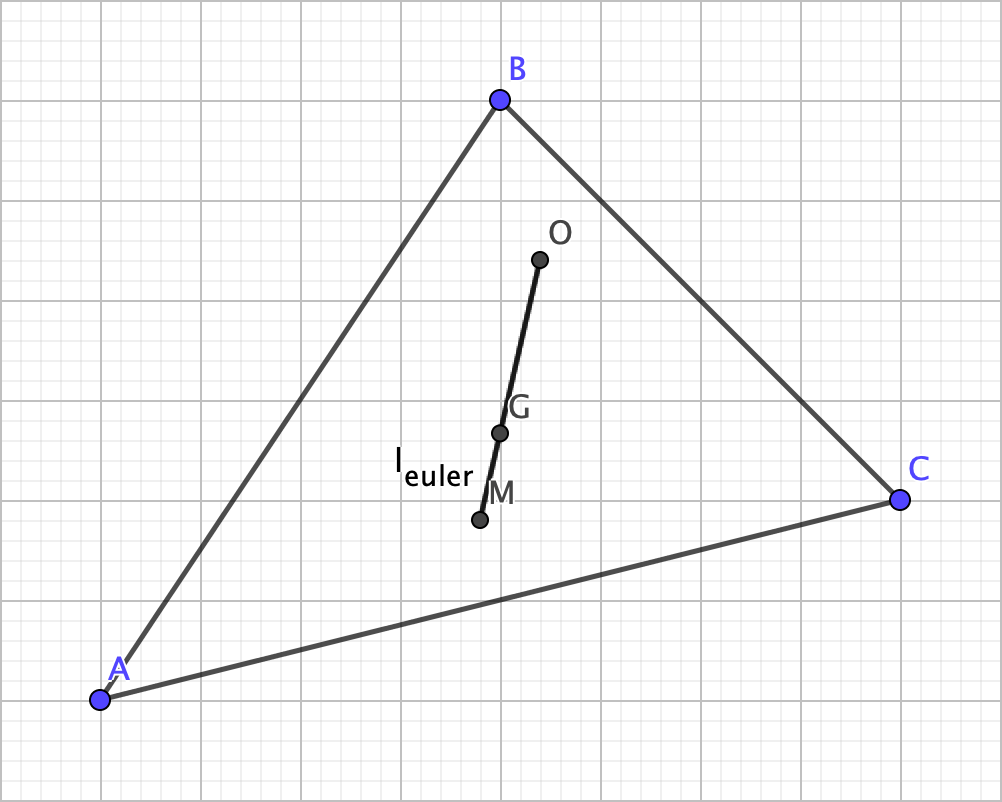

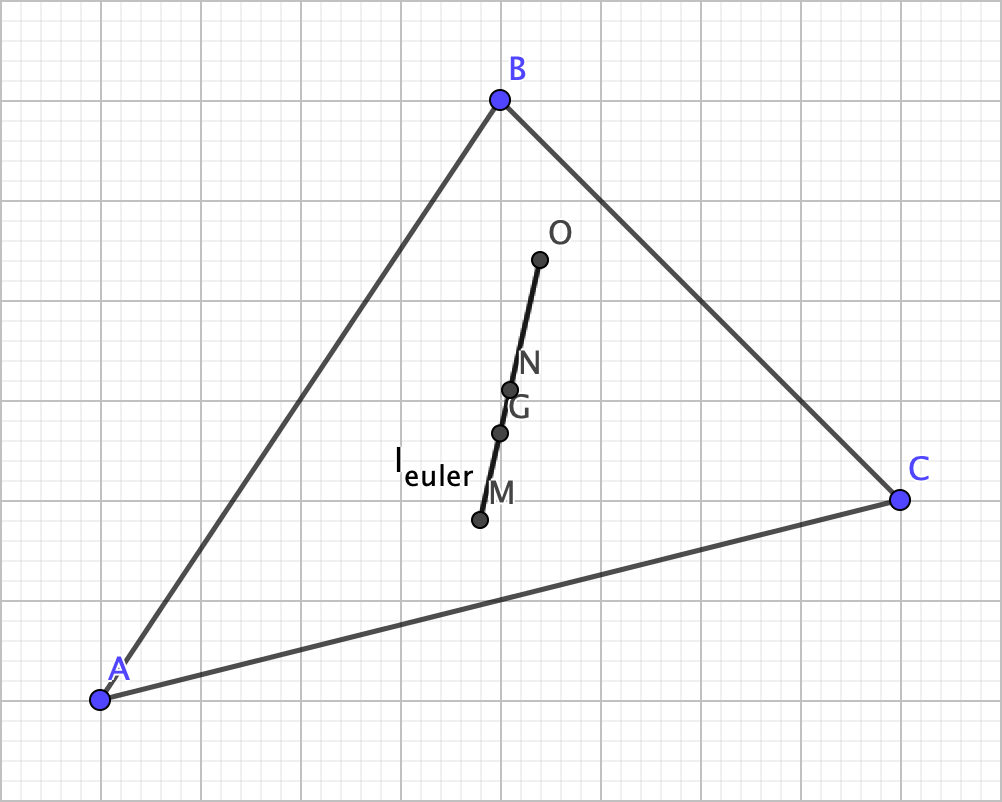

Now consider this: when constructing a line segment with the circumcenter and orthocenter as the endpoints, the centroid happens to be on the line segment (i.e. the three centers are collinear):

This line segment is referred to as the Euler line, as the eponymous mathematician Leonhard Euler discovered it himself in 1765. So, with this in mind, here’s another earth-shattering property: OG = 2 x GM. I’ll leave you to figure out how to prove this.

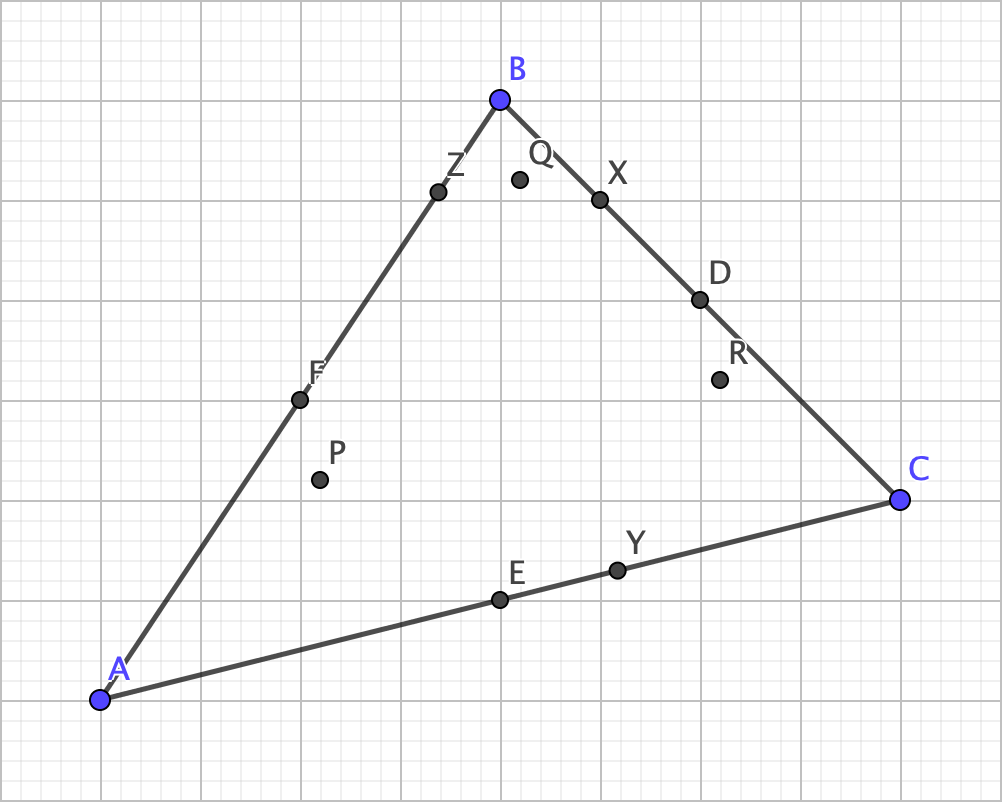

Anyhow, let’s get to the last one, and it’s probably my favorite because of how crazy the properties are. I also feel that it’s also the most overlooked because it usually doesn’t get covered in schools. First off, the midpoints of the sides are needed.

Next, the feet of the altitudes are needed (the other endpoint of the altitudes).

Lastly, the midpoints of the segments connecting the vertices and the orthocenter are needed.

Let’s look at these nine points together:

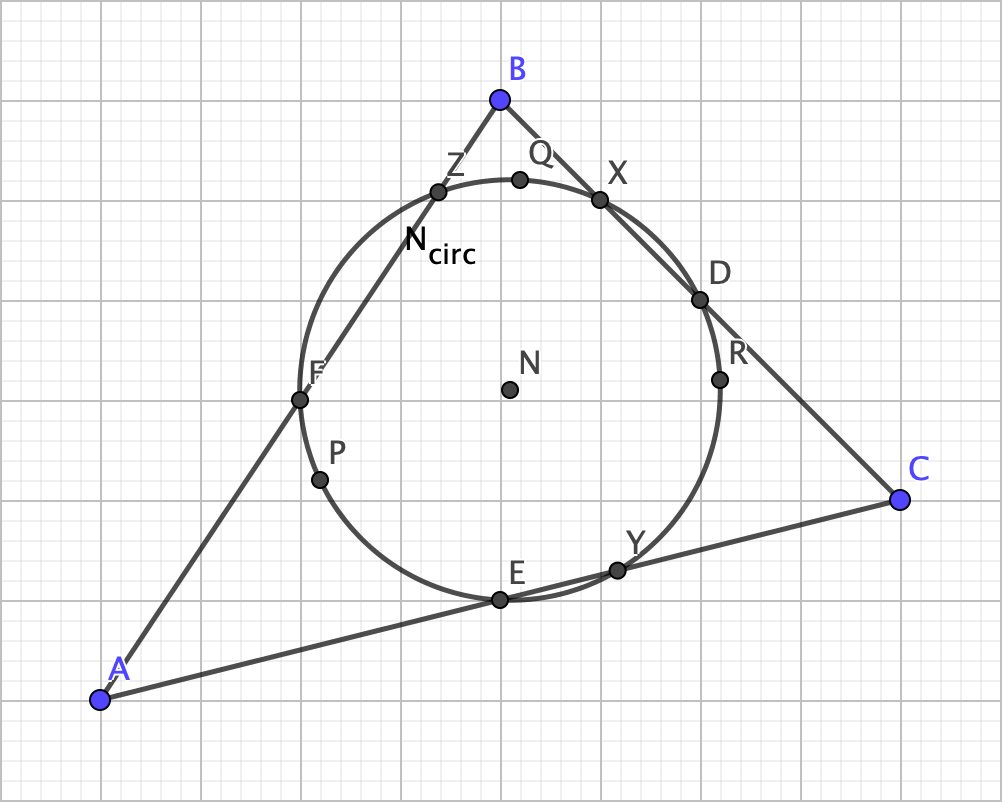

Would you believe me if they all happen to be equidistant from EXACTLY one point? Probably not. But that’s actually the case:

Crazy, ain’t it? This point that is equidistant from these nine significant points is referred to as the nine-point center, and the circle that contains that nine significant points is the nine-point circle. Here’s one other thing to blow your mind: the nine-point center is on the Euler line, and it’s also the midpoint of it as well (which I also leave for you to prove):

Anyway, I really recommend you take up learning how to construct all of this on a blank sheet of paper with just a pencil, compass, and straight edge (no rulers!). It’s quite satisfying to put together a complete image! A good starting point to learn how is to look here.

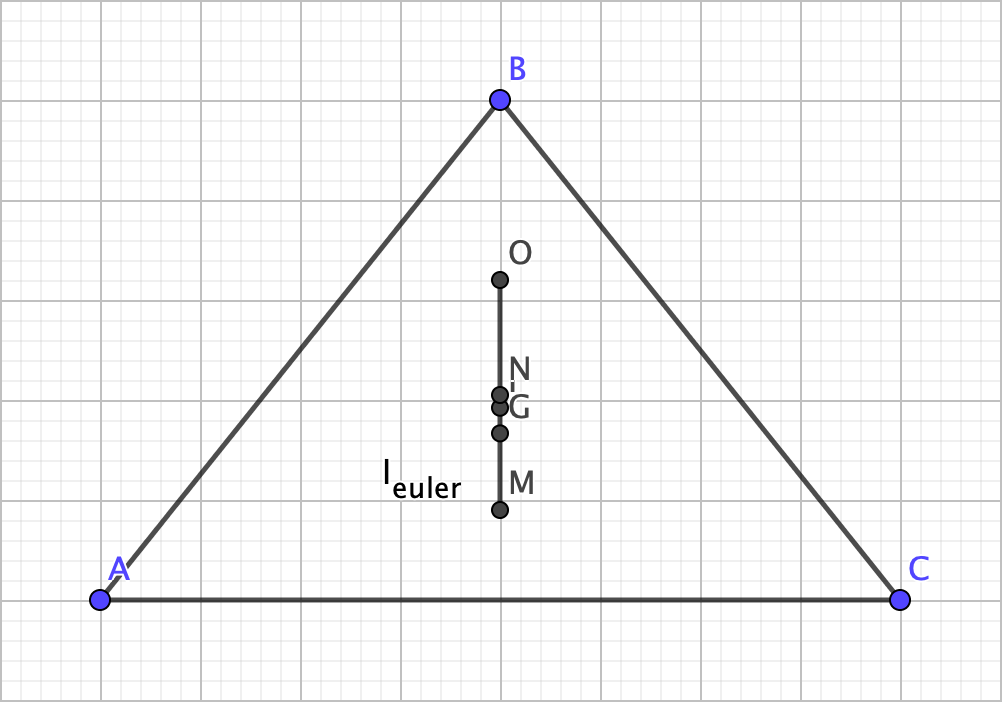

Now, you might have noticed that I haven’t yet talked about the incenter. Well, there’s a reason: it’s not always on the Euler line. There are cases, however, to which it is, and that’s when the triangle is isosceles:

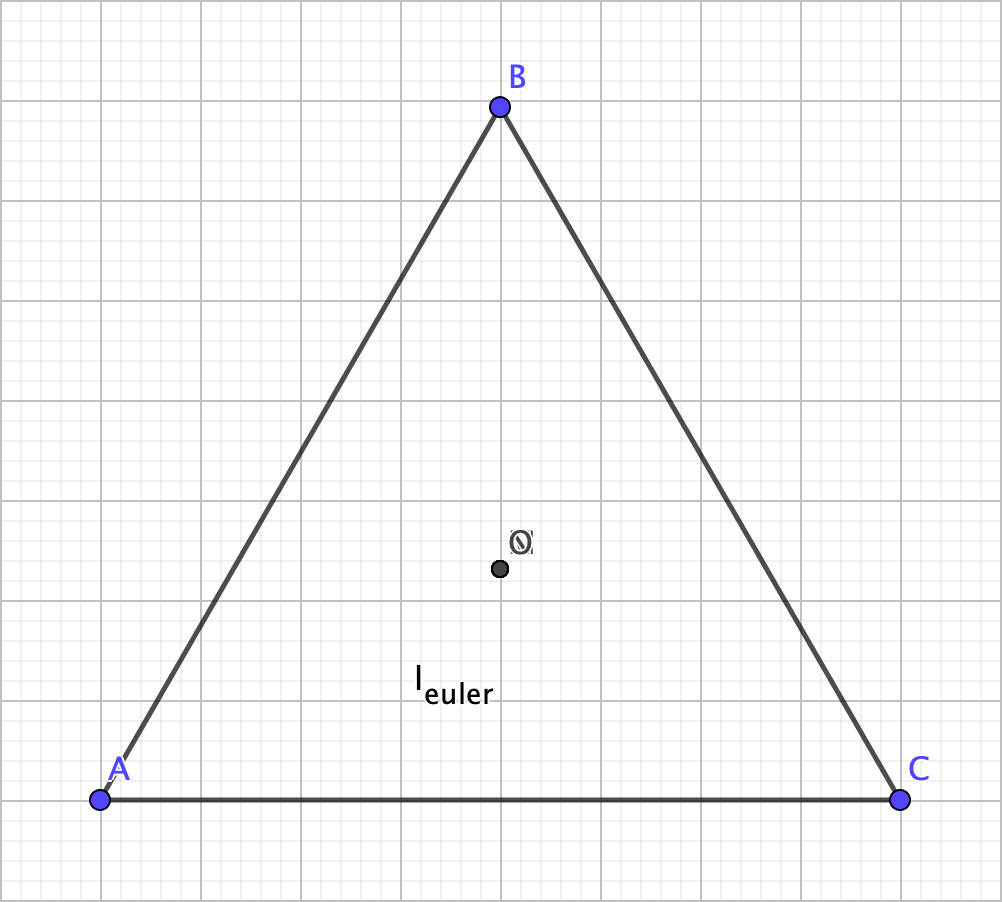

This begs the question: what happens when the triangle is equilateral?

Welp.