You’ve probably seen Latin square puzzles here or there. For example, Sudoku is one of the most popular Latin square puzzles. Sudoku even has its own derivatives: Jigsaw Sudoku and Killer Sudoku.

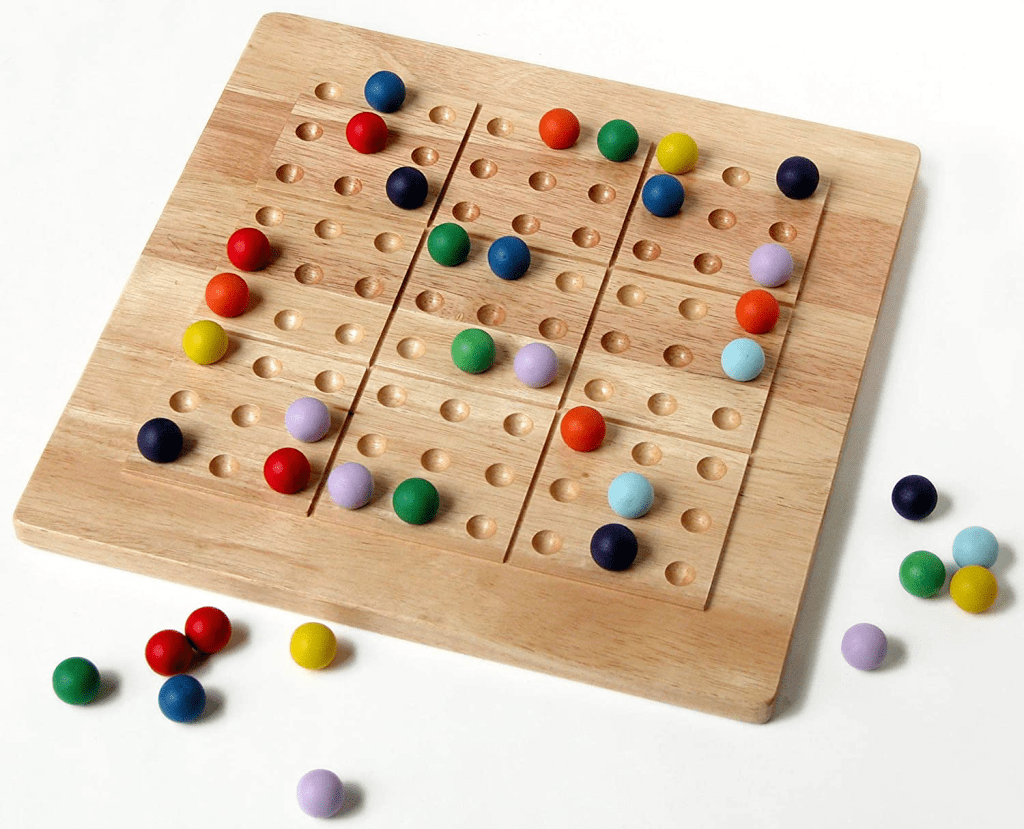

To remind you of what a Latin square is, it is an n x n arrangement of n different symbols such that each occurs exactly once in each row and each column. Numbers often make up Latin squares, although they could be replaced with something like color.

This is the case for the ColorKu board game, which is actually the same Sudoku, but in colors as opposed to numbers.

One of my former colleagues gifted me a Puzzle Baron book earlier this year on Number Logic Puzzles, which contained numerous Latin square puzzles among others. Sudoku, Jigsaw Sudoku, and Killer Sudoku puzzles were included, along with one type of puzzle of Japanese origin known as “Futoshiki” (known as Above & Below in the book), which means “inequality”, and it plays into how these puzzles are solved.

In Futoshiki, the only stipulation is that the inequality constraints are satisfied. So, for example, with the 4 next to the < symbol, only a 1, 2, or 3 can be placed there.

However, one type of puzzle was also in there, although it was under a name I didn’t recognize: Calcudoku. When I flipped through the book, I came to realize that Calcudoku was just another name for KenKen, as the name is trademarked. KenKen puzzles are featured daily in the New York Times and have surpassed Sudoku as my favorite type of Latin square puzzle (no disrespect, though, because I think Sudoku is still a very fun and intriguing type of puzzle because of the logic tricks).

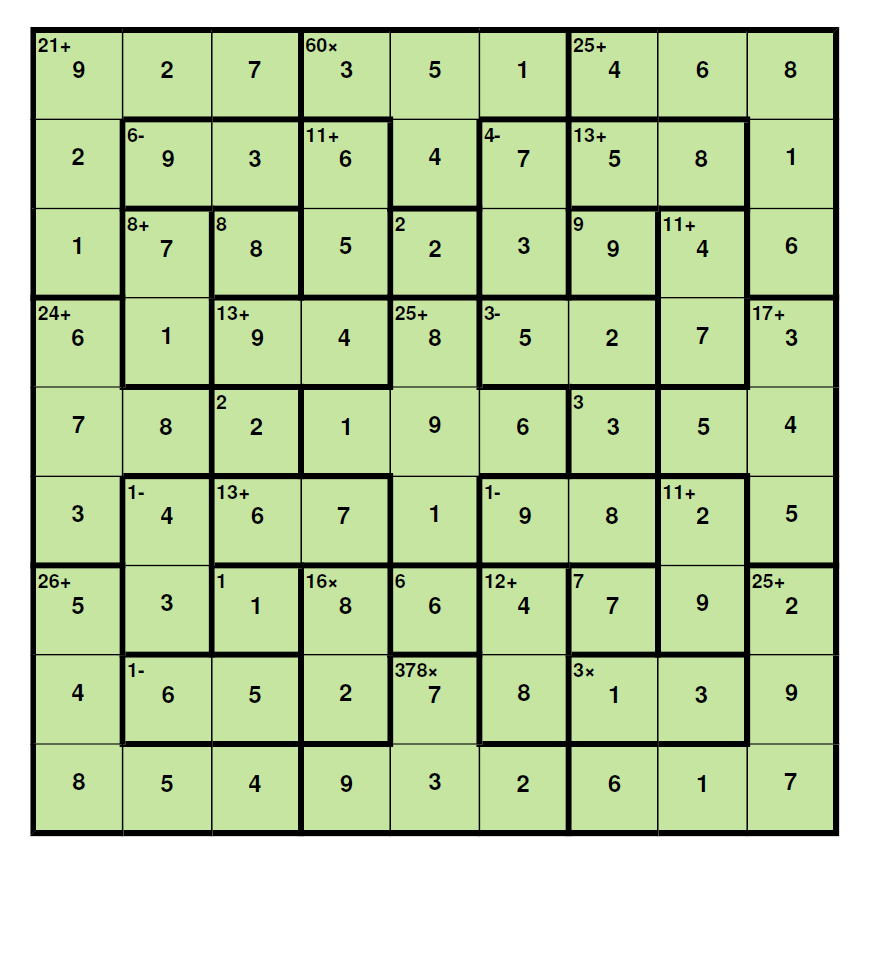

Just as with any Latin Square puzzle, the goal is to fit the numbers into the grid depending on how many rows there are. However, there are additional “cages” to every grid to which the numbers placed in there must combine to the given “target” using the provided math operation (unless it is a single-square cage, known as a “freebie”). Numbers in cages can be repeated (sometimes this is the only option) as long as the numbers repeated are not in the same row or column. How does this look in action? Well, let’s take a look at one:

So in this puzzle, there’s already a freebie: the 4 in the top right. So for starters, 4 goes there. Now, due to restrictions, I won’t be able to show the cages in proper, but I will show step-by-step where the numbers go using generic tables (I suggest you copy the actual puzzle with the cages to follow along a bit better).

| ? | ? | ? | 4 |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

There are many different directions to take from this point. For example, let’s look at the top row, as we now need to fit 1, 2, and 3. Well, given the 2/ in the top left cage (Apologies as I don’t have the weird division symbol because WordPress and I don’t know how to input Unicode on Mac yet), we know that a 3 cannot go there as 3 is not divisible by 2. Thus, there’s only one place to place 3:

| ? | ? | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

So what happens next? let’s look along the third column from the left where we already have a 3. Since we have one number in that 7+ cage, we know that the other number has to be 4 as 3 + 4 = 7.

| ? | ? | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

There now remains a 1 and a 2 to fit into that column. This is where things can get a bit interesting (and a bit wonky if you’re new, so prepare yourself). We know that we have a product in that “L”-shaped cage, and we know that a 1 and a 2 go in there (in the third column, but we don’t know where exactly yet). 1 x 2 = 2, so we need another other number in the bottom right square that, when multiplied with 2, equals 4. That number is a 2, so we can fill that bottom right square with a 2.

| ? | ? | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | ? | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? | 2 |

Because of that 2, we also now know where the 1 and 2 go in the third column:

| ? | ? | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | ? | 2 | ? |

| ? | ? | 1 | 2 |

Again, there are multiple ways to go about it from here, but I’d like to take a look at the 3- cage because there’s a property of 3- cages like these in 4×4 grids: they can only be filled with a 1 and a 4, as they are the only two numbers of 1, 2, 3, and 4 that have a difference of 3. Thus, we can use this to find important information on the second column from the left. Since a 3 cannot go in the 3- cage or the 2/ cage, the only place to place it is in the bottom row.

| ? | ? | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | ? | 2 | ? |

| ? | 3 | 1 | 2 |

As a result, we can complete the bottom row.

| ? | ? | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | ? | 2 | ? |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Additionally, due to that 3- cage, we also know where to place the 2 in that column:

| ? | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | ? | 2 | ? |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

And now we know where to place the 1 in the top row:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | ? | 2 | ? |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

From here, we can gradually fill in the numbers as there is now enough information to not rely on the clues from the cages. For example, we know where to place the last 4…

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| ? | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | 4 | 2 | ? |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

… as well as the last 2.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | ? | 4 | ? |

| ? | 4 | 2 | ? |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

With that, the rest of the grid is trivial to solve:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Here’s something to know about 4×4 puzzles: the more fluid you get, the more likely you are to solve them on any difficulty in under a minute, maybe even 30 seconds. Every day, you can solve them at kenkenpuzzle.com where you can set the parameters of the puzzles (such as size from 3×3 to 9×9, which operations you wish to include, as well as difficulty). You will either need to disable an adblocker or subscribe in order to solve any puzzle on the website, though, in addition to access the no-operation puzzles and the expert difficulty. An alternative is to solve the puzzles for the New York Times at this URL here. There are six puzzles daily: 4×4 easy, 4×4 medium, 6×6 easy, 6×6 medium, 6×6 hard, and 8×8 hard.

Why I find KenKen puzzles so fascinating is that they test your knowledge of operations and ability to deduce facts about the cages so that you know what tricks there are, such as the aforementioned property of 3- cages in 4×4 puzzles. One of the more numbers to look for in larger puzzles are 5 and 7 due to their status as primes. For example, a cage of two squares with a 14x clue should immediately indicate that 2 and 7 go in those two squares as only 2 and 7 can produce a product of 14.

These puzzles are just so fascinating to me. I’ve been solving the New York Times puzzles daily for about 2 years now, and I don’t intend on stopping anytime soon, especially considering I bought two official KenKen puzzle books filled with 9×9 expert grids.

Again, these puzzles become very elaborate as they get larger, so I encourage you all to start small today to get better so that you’ll be in shape to deduce the big ones. There’s always something satisfying about completing a puzzle that you get stuck on.

With practice, you too can conquer the 9×9’s!