Boy do I love this holiday. A good day to celebrate inner nerdiness and enjoy some good pies.

On the subject of the title image, that picture was indeed taken on Pi Day, 2012 to be precise. I had just joined my university’s math club which met every Wednesday afternoon, and we had pizza for every meeting. So it was a joyous occasion to have a pizza where the pepperonis were arranged in a “pi” formation on Pi Day.

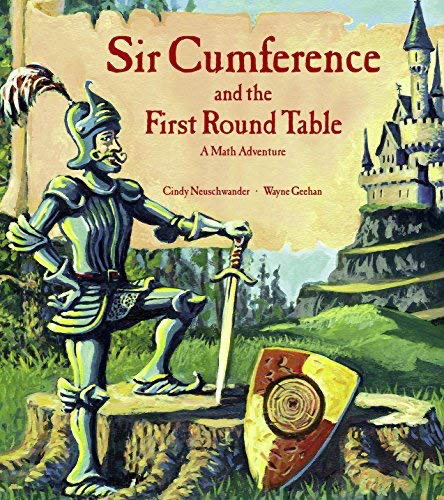

Anyhow, my memory of “pi” takes me back to third grade (or fourth grade, likely the former) when my teacher read Sir Cumference and the First Round Table: A Math Adventure for us as we learned about circles. ‘Twas a nice silly children’s book involving the eponymous knight Sir Cumference, his wife Lady Di of Ameter, their son Radius, and the making of the “first” round table. There were also the characters Geo of Metry and his brother Sym, although I can’t remember if it was this book or another one in the series that they made an appearance. Regardless, the book was a cute way to teach the terminology: Lady Di was as tall as the round portion of the table, while her son Radius was half as tall, exemplifying that the radius in a circle being the distance from the center and being half the diameter (see what the authors did there?). Even so, the concept of Pi being approximately 3.14 didn’t really come into play to my memory until fifth grade, the idea of it being “3 and a little more”.

Then came sixth grade. In my homeroom, about the walls near the ceiling were long sheets of laminated paper listing the digits of Pi, 74 of them to be precise (75 if including the three to begin it).

| 3 | . | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 5 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 8 | … |

Because we had enough time in homeroom to kind of just chill, I’d spend some time just memorizing the digits, and slowly but surely I managed to get it down, largely because the digits were sort of “bunched” in groups of 5 (spaces were made between these “groups”). However, it wasn’t until eighth grade that I could really show this off, because to prepare for the Pi Day tradition at our school, students had the opportunity to recite 100 digits, meaning I had to memorize the digits past the “0628…” that my knowledge had stopped at.

| 3 | . | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 6 | |||

| 2 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 9 | … |

Thus, the day came and plenty of folks, myself included, recited those 100 digits. One of our fellow eighth graders, who had immigrated from China earlier that year, also volunteered to recite the digits in Mandarin, the only one of us to do so, which was pretty cool. If memory serves me right, however, I might have been the only one to not stop to remember or stutter. And for whatever reason, I still remember the digits to date. They haven’t faded from memory and I don’t know why. Sometimes even I wonder why I still remember.

There also came a point (I believe in middle school) where I came to recognize Pi being irrational, i.e. no ratio of two integers can represent the number. I remember watching some sort of documentary I think at school (middle or high, can’t remember) that went into the history of Pi and the various approximations that had been made prior to its discovery of it being irrational.

It bears mentioning that high school was where I learned of how crazy Pi could actually be. Above I’ve listed a series that is related to the series I remember learning about in my AP Calculus BC class in senior year of high school, the only difference being that we got the one that leads to Pi/4, which was 1 – 1/3 + 1/5 – 1/7 + … . I think I should also note to the viewer that with any infinite series, we are not doing an “infinite sum”, rather we are evaluating the limit of the sum of infinitely many terms, and sometimes that limit does not exist (either the series diverges to positive or negative infinity OR the series simply cannot assign a value).

Regardless, I remember seeing in my Discrete Mathematics class the identity “ePi x i + 1 = 0″, which my teacher threw at us one day toward the end of our module (akin to a quarter or semester in an ordinary school, and we had seven modules in our high school that lasted about five weeks each). In my aforementioned AP Calculus BC class, we managed to prove it thanks to using infinite series.

To explain why this identity is so important, we must first discuss its special name: “Euler’s identity”. It is named after the famous Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler, who is credited with many of mathematics’s theories and discoveries, such as the solution (or, rather, the non-solution) to the Seven Bridges of Könisberg problem. He also has a number named after him, “e”, which was originally discovered by mathematician Jacob Bernoulli in the previous century. Although the number was first represented by the letter “b”, Euler himself used the letter “e” to describe it, and it would eventually become so popular as “e” that it became standard. “e” also happens to be another irrational number much like “Pi” is. Also, they are also referred to as “transcendental”, meaning they are not the root of a non-zero polynomial with rational coefficients (unlike the golden ratio, or Phi, which is a root of f(x) = x2 – x – 1).

| e | = | 2 | . | 7 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 5 | … |

So what about the other numbers in the identity? Well “i” is the imaginary unit of the complex numbers, where i is the square root of -1. As there exist polynomials that have no real roots, the complex numbers became developed to allow for at least one root, and I can talk more about them in another post. As for 0 and 1, these numbers are especially special because 0 is the additive identity (meaning any number added with 0 does not change) and 1 is the multiplicative identity (meaning any number multiplied with 1 does not change).

So, in summary, we have:

– 0, the additive identity

– 1, the multiplicative identity

– i, the imaginary unit

– e, Euler’s number

– Pi, the circular constant

The fact that these numbers can be united with one simple equation is one of the finest examples of mathematical beauty. I can get more into a proof to show that, but I think I’d need to talk a bit more about infinite series and i. Maybe then will I get into it.

Anyway, I hope y’all enjoyed this brief talk about Pi. Enjoy your pies today and remember to celebrate the coolness that is Pi!