Today would have marked our family dog’s 15th birthday, so I figured I talk about something relating to birthdays… cake!

During the lone summer I spent at grad school, I took a four-day workshop-esque class on Mathematical Modeling. One of the professors happened to be my advisor, and he tasked me with discussing and teaching envy-free cake cutting to the class with two of my classmates.

Now based on the title of this post, you might be wondering if this is a tutorial about how to cut a cake, and to that I say there’s a reason I say “with a caveat”. This is because I can only provide details on how to do specific cases, although in all fairness, I will describe how the associated procedures can be of use. I must also preface this that we are considering a way to cut a cake that is envy-free, meaning that based on the pieces given to the players at hand, no player will envy the pieces that another player has, meaning that it’s all “fair” in the end.

I first mention the case of two players. This one is probably the simplest to solve: Let one person cuts while the other picks first. This is known as “I cut, you choose”, amongst other names. Why does this work? Well, the one who cuts the cake, whom we will name Player 1, will perceive their two pieces cut to be equal in value, meaning there is no envy with the piece chosen. However, the one who chooses first, whom we will name Player 2, may not think so, so Player 2 will choose the piece that THEY think is better, removing the envy.

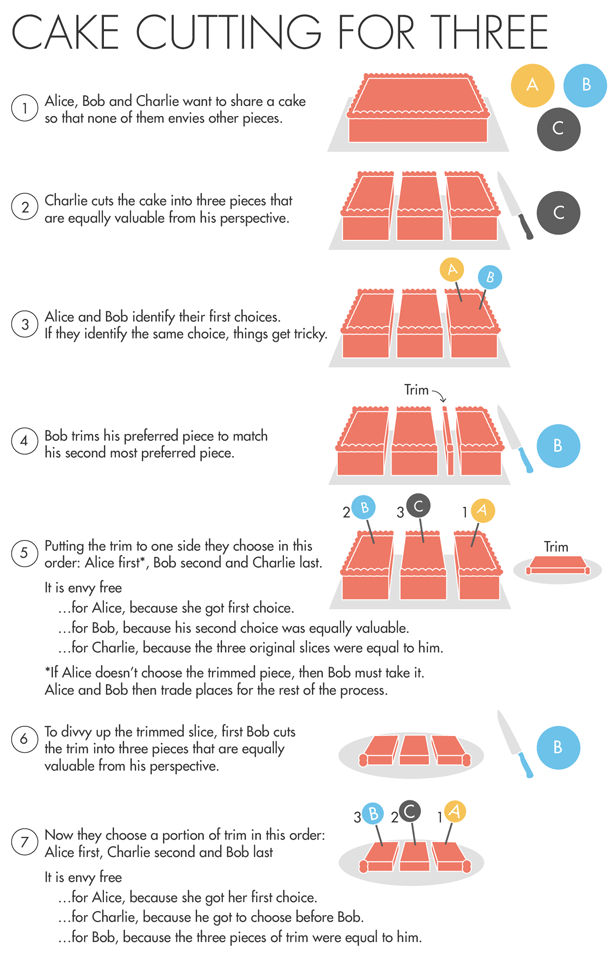

The three player problem is a bit more interesting, as it took until 1960 to solve it. The first procedure is named after mathematicians John Selfridge and John Horton Conway, with the former discovering it in 1960 and Conway discovering it later on 33 years later, although neither published it (it all relied on mathematician Richard Guy to spread the word for Selfridge).

As with the previous explanation of two people, we will consider the three people known as Players 1, 2, and 3. Player 1 starts the procedure by cutting three pieces that they perceive to be of equal size. At this point, Player 2 must examine what they perceive to be the two largest parts. If Player 2 deems them to be the same, then the honor of first choice goes to Player 3, followed by Player 2, then Player 1. This is probably the simplest sub-case of the three-player case.

However, should Player 2 perceive that there is a singular largest piece, which we will refer to as Piece A, then they take Piece A and trim it so that they perceive it to be of the same size as the second-largest piece. The newly trimmed piece is to be referred to as Piece A1 while the trimmings are referred to as Piece A2. Player 3 is then given the honors of choosing a piece (not including the trimmings, A2, which are to be discussed later). If Player 3 doesn’t choose Piece A1, then Player 2 must choose it. Player 1 chooses last regardless.

On to the trimmings, A2. Either Player 2 or Player 3 chose Piece A1, so we deem the person who chose it as Player A and the other as Player B. Player B starts the first bit by cutting Piece A2 into what they perceive to be three equal pieces. Player A chooses first, then Player 1, then Player B.

OK. That might be a lot to process, so let’s analyze how each person finished:

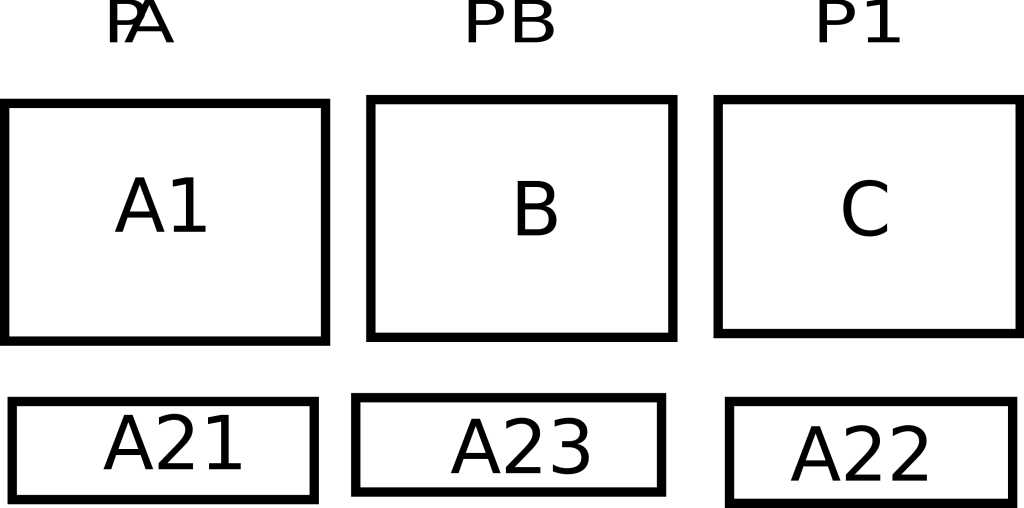

-Player A gets Piece A1 (as defined) plus the first piece of the trimmings (designated as A21)

-Player B gets Piece B plus the last piece of the trimmings (designated as A23)

-Player 1 gets Piece C plus the second piece of the trimmings

All that remains is to determine how this is envy-free.

-Player A chose what they perceived as the largest of the initial three slices, as well as the largest piece of the trimmings, so they can’t think that another player received more.

-Player B considers B to be the best of the three initial slices, hence the choice of B. Additionally, since they cut the trimmings into what was perceived as equal, there is no envy in what trimmings piece is chosen.

Player 1 is probably the most complex player to analyze. To start off, Slice C is no different from Slice B and either the same worth as Slice A1 or better.

-Player 1 cannot envy Player B, as Player 1 perceives Slices B and C to be the same. Additionally, Player 1 chose a trimmings piece before Player B, thus making A22 better or the same as A23.

-Player 1 cannot envy Player A as they perceived the initial Slice A the same as the eventual choice Slice C. As A1 plus all of the trimmings pieces A21, A22, and A23 make up the initial Slice A, Player 1 perceives Player A’s total as less than or equal to their own.

Here’s another way to look at it, with a visual way to picture it:

And there you have it. I’d like to try this with people at some point to see it in practice.

Lastly, I’d like to dedicate this post to our family dog of 14+ years, Snowball.