It should come to no surprise that I enjoy puzzle squares.

During grad school, I came to appreciate math puzzle squares thanks to the classes I took. What’s funny is that I actually discovered KenKen (the puzzle I discussed in the last blog) in my Mathematics in Pop Culture and Media class, although I didn’t really give it much focus until I landed my first job about a year later.

Anyhow, there are two types of 3×3 puzzle squares I’d like to discuss that I think can provide some more meaningful practice for students in middle school. The first has an actual specific name: MATHadazzle. These puzzles are featured in a series of books that are aptly titled, “MATHadazzles! Mind Stretch Puzzles” which each volume featuring a numerical topic (Numbers, Integers, Fractions, Decimals, etc). One of the authors happened to give a talk at my grad school and talked about enrichment strategies in the classroom, and there were opportunities to win some of the books for free. As it turns out, I happened to win the third volume on integers.

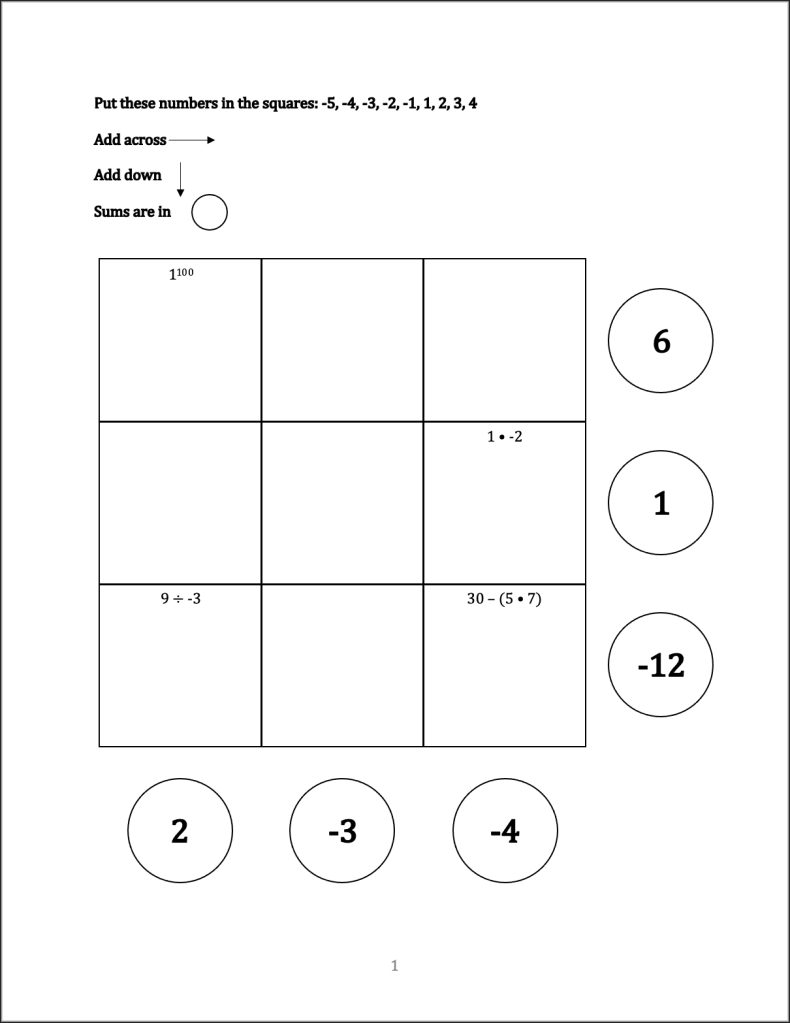

So what does a MATHadazzle puzzle look like? Well, it’s a 3×3 puzzle grid to be filled with the a fixed set of numbers (for Volume 3 on Integers, this set was -5, -4, -3, -2, -1, 1, 2, 3, 4), and each number must be used exactly once. Some of the squares have a clue as to which number is to belong in that square, such as “prime number” or “5 – 3” (the clues could be a number classification or math expression). Furthermore, at the very right of each row and bottom of each column denoted the sum of the numbers in that row or column in a circle. So one would look like this:

To start, 1100 simplifies to 1, so 1 goes in the top left square.

| 1 | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? |

Next 9 / -3 = -3, so -3 belongs in the bottom left square.

| 1 | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | ? |

| -3 | ? | ? |

To solve the square between the 1 and -3, we add 1 and -3 to get -2. The missing number must add with -2 to get 2, meaning the missing number is 4.

| 1 | ? | ? |

| 4 | ? | ? |

| -3 | ? | ? |

1 x -2 = -2, so that square has -2.

| 1 | ? | ? |

| 4 | ? | -2 |

| -3 | ? | ? |

With the middle square, 4 + -2 = 2, and we need a number to combine with 2 to get 1. 2 + -1 = 1, so the number in the middle is -1.

| 1 | ? | ? |

| 4 | -1 | -2 |

| -3 | ? | ? |

With the last clue, we have 30 – (5 x 7). This simplifies to 30 – 35, which is -5, so we now have that square solved.

| 1 | ? | ? |

| 4 | -1 | -2 |

| -3 | ? | -5 |

Let us solve for the number between -3 and -5. These two numbers sum to -8, but we need another number to get to a sum of -12. That number is -4.

| 1 | ? | ? |

| 4 | -1 | -2 |

| -3 | -4 | -5 |

For the remaining two, we use the column sums. For the middle column, we have -1 + -4 = -5. The column sum is -3, so we need an extra 2.

| 1 | 2 | ? |

| 4 | -1 | -2 |

| -3 | -4 | -5 |

Only one number has not been used: 3. Let us check the row sum and column sum. 1 + 2 + 3 = 6, so the row sum checks out. 3 + -2 + -5 = -4, so the column sum also checks out. Thus, we have solved our puzzle:

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | -1 | -2 |

| -3 | -4 | -5 |

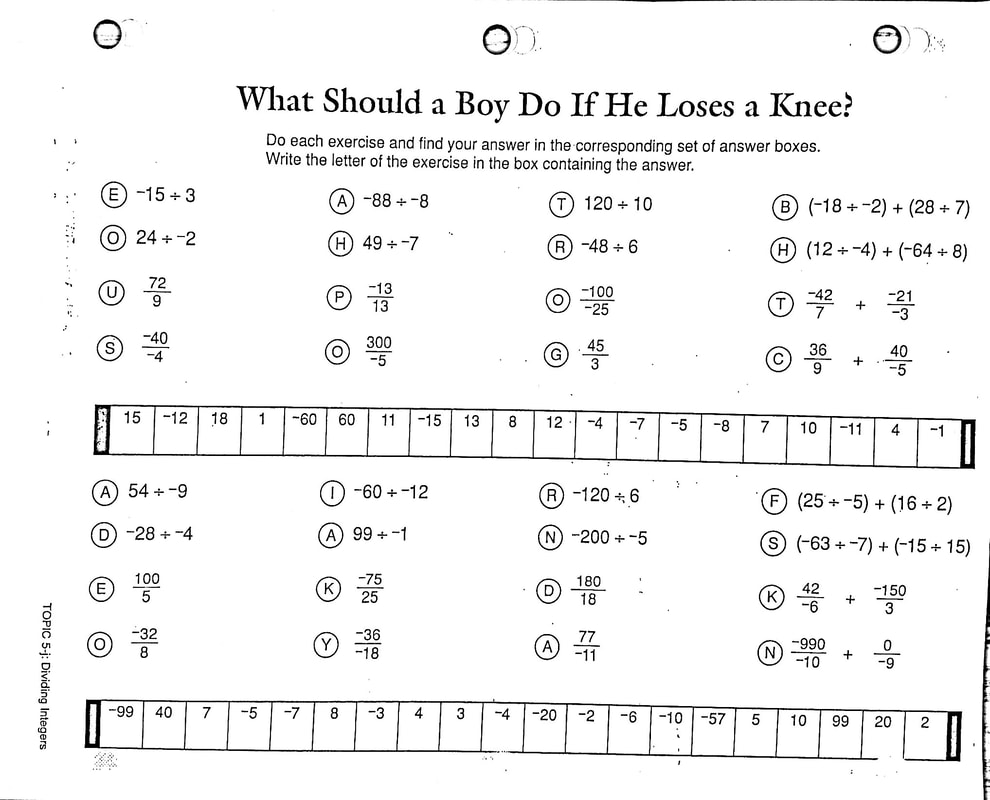

The significance of these puzzles for me is that these would come to my advantage when I had my second student teaching practicum at The School at Columbia University, a private K-8 school near campus. I was sorted to be the student teacher for seventh grade (which meant Pre-Algebra), and my cooperating teacher had supervised quite a few of my peers. As I began during the fall, the students were going to be starting off with learning integer operations. My cooperating teacher had various academic enrichment activities for students to engage in, and it was for students who were curious and wanted to better their own knowledge, albeit for no additional credit. As the students were academically motivated, quite a few of them would take up this challenge. That being said, my cooperating teacher had me design my own activity as a way to help the students get to know me a little better. I actually struggled to think of something before recalling I owned the MATHadazzle book, but then adapting it into a unique activity was another challenge altogether. However, given that the students were also solving these exercises from a book series, Math with Pizzazz, I figured how to stretch my activity even further.

I remember solving these goofy exercises when I was a student, and the charm that resonated with me from that time also happened to resonate with the students: the pun that answers the question posed at the beginning. For the example I have here, the coded message is “GO TO A BUTCHER SHOP AND ASK FOR A KIDNEY” (I apologize for the massive cringe, because I had to go through it as well).

To start the process of making the activity, I had to recreate the puzzles one-by-one (78 total), but then I decided to associate each puzzle solution with a letter. Each letter would fill into a coded message that upon completion, would reveal a message, and it tied into a theme for the activity: a bakery. Each would be sorted into six groups of thirteen each, with each group being associated with a pastry (I chose Snickerdoodles, Glazed Donuts, Morning Buns, Cream Puffs, Egg Tarts, and Turnovers). Thus, the students would effectively be “baking” in the MATHadazzle bakery. To further this, at the top right corner of each puzzle was a picture of the pastry of that the puzzle group.

Now what was the eventual code? “WANT TO MAKE A PASTRY PUN? IT’S A CAKEWALK! IF YOU HALF-BAKE IT, THOUGH, IT WILL LOAF AROUND LIKE BREAD.” (I’m not sorry about that one)